An inventory valuation method is the accounting rulebook you use to figure out the dollar value of all the products you have sitting on the shelf. This isn't just some boring number for your accountant; it's a strategic decision that echoes through your entire business, shaping your reported profits, your tax bill, and how healthy your company looks on paper.

Choosing how you value your inventory is one of the most important financial calls an e-commerce owner will make. Think of it less as a bookkeeping chore and more as a strategic choice that tells a story about your business's performance. The method you land on directly sets your Cost of Goods Sold (COGS), which then determines your net income and, you guessed it, how much you owe in taxes.

Let's make this real. Imagine you sell widgets. You bought 100 in January for $10 each. Come March, costs went up, so you bought another 100 for $12 each. Now, when a customer buys one widget, which cost do you use for that sale? Do you pull from the older $10 batch or the newer $12 batch? How you answer that simple question changes your whole financial picture.

The ripple effects of this decision are huge. Lenders, investors, and potential buyers will all be combing through your financial statements to see how stable and profitable you are. The right inventory valuation method paints a clear, consistent picture of your business, while the wrong one can seriously warp reality.

Here are the key areas your choice will hit:

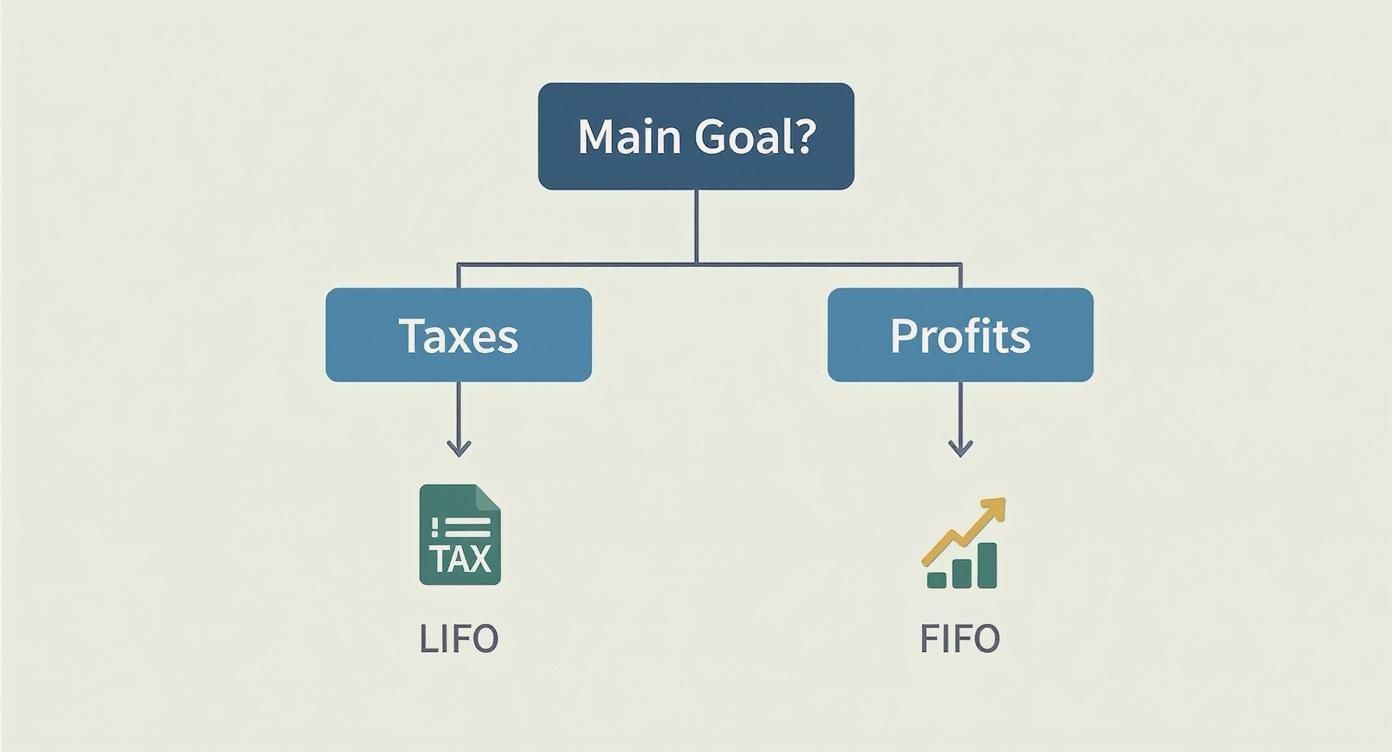

This choice isn't just about being compliant; it's about financial strategy. The method you select should line up with your goals, whether that’s showing investors the highest possible profits or minimizing your tax hit to keep more cash in the business.

Of course, accurate valuation starts with tracking every single cost that goes into your inventory. We're not just talking about the purchase price. You need to account for freight, handling, and any import duties. For DTC brands sourcing from overseas, properly managing import VAT from China is a critical piece of the puzzle to get your true inventory cost right.

Ultimately, your inventory is one of your biggest assets. To get the full picture, you have to know where you're starting from. Understanding how to calculate beginning inventory is the first step before you can even apply a valuation method. This guide will walk you through the three main methods—FIFO, LIFO, and Weighted Average—so you can confidently pick the right approach for your online store, even if you use a 3PL to handle your fulfillment.

The First-In, First-Out (FIFO) method is probably the most intuitive inventory valuation method out there because it perfectly mirrors the natural, physical flow of goods. Just think about the milk aisle at the grocery store—employees are always stocking the newest cartons at the back and pushing the oldest ones forward. This ensures the first ones in are the first ones out, long before their expiration dates.

FIFO applies that exact same logic to your accounting. It runs on a simple assumption: the first products you bought (First-In) are the first ones you sold (First-Out). This means your Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) will always be based on the cost of your oldest inventory. Meanwhile, the inventory left on your balance sheet is valued at the cost of your newest purchases.

Let's walk through how this plays out for a DTC brand selling premium coffee mugs. Imagine these were your inventory transactions for the first quarter:

Now, let's say you sold a total of 200 mugs during that quarter. How do we figure out your COGS and the value of what's left using FIFO? Easy.

Add them together, and your total Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) for the quarter comes out to $500 + $600 = $1,100. For a more detailed breakdown, you can check out our practical guide on how to compute FIFO.

After selling those 200 mugs, you need to know the value of what’s still sitting on the shelves. Let's look at what's left:

So, your ending inventory value is $300 + $650 = $950. This is the number that will show up on your balance sheet, giving a snapshot of your inventory's value based on the most recent prices you paid.

Key Takeaway: With FIFO, your balance sheet gives a much more accurate picture of your inventory's current replacement cost. This is a huge plus when you're looking for a loan or showing your financials to potential investors.

Choosing FIFO isn't just an accounting exercise; it has real financial consequences, especially when your costs are fluctuating. Since you're matching older, cheaper costs against your current revenue, FIFO tends to report a higher gross profit during periods of inflation. On paper, this makes your business look more profitable.

But there's a catch. A higher reported profit means a higher taxable income, which in turn leads to a larger tax bill. It’s a classic trade-off every business owner needs to weigh.

Despite this, FIFO remains one of the most widely used inventory methods around the globe, and for good reason. It’s logical, it aligns with how most businesses physically manage their stock, and it's accepted under both U.S. GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles) and IFRS (International Financial Reporting Standards). This makes it a safe, reliable, and transparent choice for many e-commerce brands.

While FIFO logically follows the physical movement of goods for most businesses, the Last-In, First-Out (LIFO) method flips that idea on its head for accounting purposes. LIFO operates on an assumption that feels counterintuitive at first but offers some powerful financial advantages, especially in the United States.

Think about a big pile of sand at a construction site. When a worker needs a scoop, they take it from the top—the last sand added is the first to be used. The LIFO inventory valuation method applies this exact same principle to your costs. It assumes that the most recently purchased inventory (Last-In) is the first stuff you sell (First-Out).

In practice, this means your Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) gets calculated using the cost of your newest inventory, while your ending inventory is valued based on the cost of your oldest stock.

Let's revisit our DTC brand selling premium coffee mugs and see what happens when we apply the LIFO method to the same sales period. You'll see just how much the financial picture can shift.

Here’s a quick recap of the inventory purchases:

The company sold 200 mugs during the quarter. With LIFO, we start with the most recent purchases and work our way backward.

Add them up, and your total Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) for the quarter under LIFO is $650 + $600 = $1,250. Take a look back—this is $150 higher than the COGS we calculated with FIFO. That's a pretty big difference, and it's all due to the accounting method we chose.

So, why would anyone use a method that results in a higher COGS? The primary appeal of LIFO lies in its tax benefits, especially during periods of rising costs (hello, inflation!). By matching your most recent—and typically highest—costs against your current revenue, LIFO results in a higher COGS.

This, in turn, leads to lower reported gross profits and, consequently, a lower taxable income. For businesses laser-focused on managing cash flow, this tax deferral is a major strategic advantage.

LIFO’s strength is its ability to smooth out earnings during periods of price volatility, which is why it has been a recognized accounting practice in the U.S. for decades.

This method was formally authorized in the U.S. all the way back in the Revenue Act of 1939. Accountants have long recognized its ability to provide a more accurate picture of earnings when prices are on the move. You can learn more about the history and benefits of LIFO accounting on jofa.com.

But this popular U.S. method comes with some big strings attached. LIFO is strictly banned under International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), which makes it a non-starter for companies operating globally or those that need to follow international accounting rules. You can explore the strategic differences in more detail in our guide comparing FIFO vs. LIFO for retail stores.

One of the biggest trapdoors with LIFO is a phenomenon called LIFO liquidation. This happens when your company sells more inventory than it purchases during a period, forcing you to dip into those older, lower-cost inventory layers to calculate COGS.

When that happens, those ancient, cheap costs get matched against today's higher revenues, creating an artificial and often massive spike in reported profits. This can trigger a surprisingly large tax bill and completely distort your company's true performance for that period, making financial analysis a nightmare. It’s a risk that demands careful inventory management to avoid getting burned.

If FIFO and LIFO feel like they sit at opposite ends of the spectrum, the Weighted Average Cost (WAC) method is the happy medium. It offers a blended approach that smooths out the bumps of price volatility, making it a popular and practical choice for many eCommerce brands.

Think of it like making a big batch of cold brew. You pour in coffee beans you bought at different times and for slightly different prices. Once they're all mixed together in the steeping bin, you can’t tell which bean came from which bag. Every cup of coffee you pour has the same blended, average cost. That’s the simple idea behind WAC.

The beauty of WAC is its simplicity. Instead of juggling multiple cost layers for every purchase, you calculate a single average cost for all identical items in your inventory. This one number becomes your go-to for figuring out both your Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) and the value of your remaining inventory.

The formula is refreshingly straightforward:

Total Cost of Goods Available for Sale / Total Number of Units Available for Sale = Weighted Average Cost Per Unit

This simple calculation is a major part of its appeal. It avoids the complexities of tracking specific batches, which is a lifesaver when you're dealing with large quantities of identical products.

Let's check back in with our DTC coffee mug brand and run the numbers using the WAC method.

Inventory Purchases:

First, we need to find the total cost and total number of mugs available during the quarter.

Now, we just plug those numbers into the WAC formula: $2,050 / 350 units = $5.86 per mug (rounded).

With our single average cost of $5.86, the rest is easy. This one figure applies to every single mug, whether it was sold or is still sitting on a warehouse shelf.

If the company sold 200 mugs during the quarter, the math is clean:

For those who want to get deeper into the mechanics, our detailed guide on how to calculate weighted average cost walks through more examples step by step.

Financially, the WAC method lands right in the middle ground between FIFO and LIFO. When your costs are rising, WAC will give you a higher COGS than FIFO but a lower one than LIFO. Unsurprisingly, your reported profits and tax obligations will also fall somewhere in between.

This "smoothing" effect makes your financial performance look more stable and less prone to the sharp swings caused by price changes.

Advantages of the WAC Method:

WAC is an especially great fit for businesses that sell large volumes of identical, non-perishable items where tracking the cost of each specific unit would be a nightmare. By blending all your purchase costs into a single average, WAC offers a pragmatic and dependable way to value your inventory.

Okay, we've waded through the theory of FIFO, LIFO, and WAC. Now for the million-dollar question: which one is right for your business?

Picking an inventory valuation method isn't just about satisfying your accountant. It's a strategic move that directly impacts your bottom line, how investors see your company, and even your tax bill. There’s no single “best” method—only the one that aligns with your financial goals, operational reality, and the kinds of products lining your shelves.

Think of it as choosing the right tool for a specific job. You wouldn't use a hammer to turn a screw. Similarly, the right inventory method depends entirely on what you're trying to build.

Before you plant your flag on a particular method, you need to take an honest look at your business from a few different angles. Each of these factors can nudge you in one direction or another, so it’s crucial to see how they all fit together.

Here are the big questions every e-commerce brand needs to ask:

A lot of e-commerce brands get tripped up here. They wonder how using a third-party logistics (3PL) partner affects their choice of inventory method.

The good news? It really doesn't. Your 3PL’s physical inventory process is totally separate from your accounting cost flow.

Most 3PLs operate on a physical FIFO basis by default. They ship the oldest units first to keep products fresh and avoid obsolescence. But that doesn't lock you in. You are completely free to use LIFO or Weighted Average on your books for your financial reports.

Think of it this way: your 3PL manages the boxes, while your accounting system manages the cost layers associated with those boxes. As long as your records are clean, you can apply any of the accepted valuation methods, no matter which physical unit your fulfillment center actually picks and packs.

To make this crystal clear, let's tie each method to a primary business driver.

To help you visualize the trade-offs, we've put together a simple decision matrix.

This table breaks down how each method aligns with common business goals and characteristics, helping you pinpoint the best fit for your e-commerce brand.

Ultimately, choosing your inventory valuation method is a foundational decision. It shapes your profit reports, your tax obligations, and how banks and investors view the health of your business. By carefully weighing these factors against your long-term vision, you can pick a method that not only keeps you compliant but also acts as a strategic lever for growth.

Even after you've got the basics down, picking an inventory valuation method inevitably brings up a bunch of "what-if" scenarios. Let's tackle the most common questions we see from e-commerce owners to help you navigate the practical side of these decisions.

Yes, but it’s definitely not a casual decision. In the United States, you can't just flip-flop between methods to make your numbers look better in a given quarter. Changing your accounting method is a formal process that requires filing IRS Form 3115.

You’ll need a legitimate business reason for the switch, like a major change in your business model or adopting a new industry standard. The process usually involves restating your past financial records to reflect the cumulative effect of the change, which is why it's crucial to work with a CPA to make sure you're doing everything by the book.

Lenders and investors live and breathe financial metrics, and your choice of valuation method directly impacts what they see. When you're trying to secure a loan or attract capital, the health of your financial statements is everything.

During times of rising costs, FIFO makes your business look stronger on paper. It reports higher net income and a healthier balance sheet because your remaining inventory is valued at more recent, higher prices. This can make your brand appear more profitable and asset-rich, which is exactly what lenders like to see. LIFO, on the other hand, reports lower profits but saves you money on taxes. Be ready to explain your logic either way.

Key Insight: Lenders care about consistency and profitability. While LIFO saves on taxes, FIFO often paints a more attractive picture for securing financing because it demonstrates higher gross margins and asset values during inflation.

This little decision tree breaks it down perfectly.

If your main goal is tax optimization, LIFO is your path. If it's all about maximizing reported profits, FIFO is the clear winner.

Nope. This is a super common point of confusion, but your 3PL’s warehouse operations have zero bearing on your accounting method.

Most fulfillment centers ship goods on a physical FIFO basis—it just makes sense operationally. Moving the oldest stock out first minimizes the risk of products expiring or becoming obsolete. But the physical flow of your goods is completely separate from the cost flow you use in your accounting.

You can absolutely use LIFO or Weighted Average for your financial reporting, even while your 3PL partner ships the oldest units first. The trick is to keep immaculate records of your purchase costs and dates in your inventory management system. That system is your single source of truth for all things accounting.

Think of the specific identification method as the most hands-on, granular approach possible. It involves tracking the exact cost of each individual item from the day you buy it to the day you sell it.

This method only makes sense for businesses selling unique, high-value items that are easy to tell apart. We’re talking about an art gallery selling one-of-a-kind paintings, a car dealership tracking vehicles by their VINs, or a jeweler selling custom-made rings.

For a typical e-commerce store juggling hundreds or thousands of identical SKUs, this method is an operational nightmare. The record-keeping would be insane. It's precisely why the vast majority of online brands stick with FIFO, LIFO, or Weighted Average Cost—they are practical, scalable ways to handle cost accounting for large volumes of similar products.